- 2019/2020 Recap: Lady Scots Conquer First Round of CIF!

- 2019 Recap: Justin Flowe Wins the Dick Butkus Award

- Upland Lady Scots Have Their Revenge

- What is BBCOR?

- Tommy John, A Name To Be Feared

- The Game Plan

- Too Much Tackle?

- Is Cheer A Sport?

- Transgender Inclusion in Youth Sports

- Are You Counting Sheep Right?

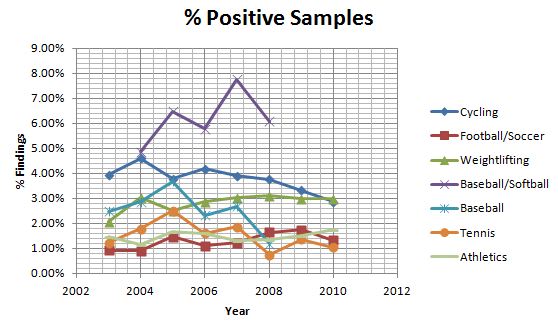

Cycling and the Prevalence of Doping

- Updated: July 28, 2014

In 2013, Armstrong admitted to doping in all seven Tours in an interview with Oprah Winfrey. Six of the seven overall runners-up (all except Joseba Beloki in 2002) have admitted or been found guilty of doping. So, if everyone was doping, then no one had an unfair advantage and those that placed still placed. However, if you wanted to place at all you had to dope, it was the difference between placing 1st and placing 100th. The entire system of doping and denying not only risked all of the riders’ safety and health, it undeniably tarnished the integrity of the sport.

Recent posts made by Sub Solution, explores how drug use in cycling has existed since before the first Tour de France in 1903. Only the last two years have really been free of steroid use and blood transfusions. The world’s first long-distance road race took place in November 1869. French reporter and author, Pierre Chany, followed 49 Tours before his death in 1996, and he simply said “[Drug use] existed, it has always existed.” The 1976 Tour winner, Joop Zoetemelk, spoke about his blood transfusions in an interview right after winning the 9th and 10th stages. At the time, it was considered a necessary medical aid in the race. The Tour de France is cycling in its extremes both in distance and in speed, pacing motorcycles and cars. Even for the strongest athletes, six days of cross country racing is exhausting, perhaps even boring. Riders used everything from alcohol and ether to blood transfusions and drugs to dull the pain, increase oxygen circulation, and deal with the long stretches of time.

In the early Tour de France, the strongest drug available was strychnine. Riders would also deaden the pain with incredibly strong alcohol. As late as the 1960s, riders would tie handkerchiefs soaked in ether under their chins. Another frequent treatment included nitroglycerine which is used by doctors to restart the heart after cardiac arrest. Supposedly, nitroglycerine improves the riders’ breathing. It also contributes to the hallucinations already caused by exhaustion; American champion Major Taylor dropped out of a race afraid for his safety, “there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand.” Drug use was so commonplace that the rule book printed in 1930 reminded national teams that drugs were not provided by the race.

In the 1970s, steroids became commonly used, not to build muscle mass, but to speed recovery and allow competitors to train harder and longer. To avoid detection, riders used erythropoietin, also called EPO, which increases red-cell production in individuals sick with anemia. Red blood cells transport oxygen throughout the body, so blood transfusions and increased red blood-cell production give athletes an advantage in high altitudes where there is less oxygen and when their body needs it more for the work it is doing. However, there have been cases where riders received someone else’s blood in transfusions that got mixed up or blood so thick the heart couldn’t pump it throughout the body. In some cases blood stored for too long resulted in cyclist’s death. In 2006 and 2007, many riders were exposed or confessed to using EPO resulting in the loss of many Tour titles.

The first attempts to regulate drug use began with Pierre Dumas, who campaigned for the testing and suppression of doping, or drug use, in cycling as well as at the Olympic level. At this time, cyclists were not prohibited from using blood transfusions, hormones, alcohol, ether, or other drugs prescribed by their doctors to successfully complete the Tour. Even when Dumas found the eventual winner of the 1960 tour, Gastone Nencini, in bed with a plastic tube in each arm connected to a bottle containing hormones, the injection was not illegal. Few cyclists were disqualified or even sanctioned for this kind of doping. When Knud Enemark Jensen collapsed during the 100km team time trial at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, however, Dumas led a committee of doctors who demanded drug testing at the Olympics. France then outlawed performance-enhancing drugs and began anti-doping testing at the 1966 Tour. Riders actually staged a protest during the tour in response to the drug testing: “No dope, no hope.” Some even asserted that the Tour is only possible because of doping. Yet, questions of health, integrity and sportsmanship are all compromised by doping.

Since 1961, 56% of winners have tested positive or confessed to doping. If those who tested positive but never sanctioned are included, 68% of winners used doping. Lance Armstrong led the US Postal Service cycling team in seven consecutive titles from 1999-2005. However, the USADA has since discovered that Armstrong and the entire team were using blood transfusions, testosterone, EPO and other performance-enhancing drugs.  Armstrong repeatedly denied allegations, he explained positive tests with claims to be using prescribed cortisone cream, and officials may have even been bribed to ignore positive tests. In 2012, it was also discovered that Armstrong had been involved in a massive doping scheme, in part forcing all of his teammates to use EPO. Only one of the cyclists who placed in the Tour de France between 1999 and 2005, Fernando Escartín, was not involved in the doping. Armstrong used EPO, received multiple blood transfusions, and gave out testosterone patches to his teammates. He lied to everyone but his doctor when he was in the hospital for cancer treatment. Consequently, Lance Armstrong has been stripped of all of his titles since August 1998. While other riders have been banned for a couple of years, Armstong has been banned for life and the titles for those years have not been awarded to anyone else. It was exciting see the average race time get faster and faster but I think it will be exciting to see someone win the tour seven years in a row without blood transfusions. Perhaps, the next 100 Tours will do better and cyclists will not only endure but race with integrity as well.

Armstrong repeatedly denied allegations, he explained positive tests with claims to be using prescribed cortisone cream, and officials may have even been bribed to ignore positive tests. In 2012, it was also discovered that Armstrong had been involved in a massive doping scheme, in part forcing all of his teammates to use EPO. Only one of the cyclists who placed in the Tour de France between 1999 and 2005, Fernando Escartín, was not involved in the doping. Armstrong used EPO, received multiple blood transfusions, and gave out testosterone patches to his teammates. He lied to everyone but his doctor when he was in the hospital for cancer treatment. Consequently, Lance Armstrong has been stripped of all of his titles since August 1998. While other riders have been banned for a couple of years, Armstong has been banned for life and the titles for those years have not been awarded to anyone else. It was exciting see the average race time get faster and faster but I think it will be exciting to see someone win the tour seven years in a row without blood transfusions. Perhaps, the next 100 Tours will do better and cyclists will not only endure but race with integrity as well.

For more information about doping, http://www.usada.org/athletes/youth-olympic-games/.

Jonathan Vaughters, former cyclists, speaks passionately about anti-doping. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/12/opinion/sunday/how-to-get-doping-out-of-sports.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Author: Melanie Carbine

Melanie Carbine currently writes for several education blogs, vlogs about her travels, and teaches middle school in the DC Metro Area.

Copyright © 2023 KSNN. All rights reserved.